Good, so there’s GrapheneOS on my Pixel 8 now. Like on my previous Pixel 6 with LineageOS, I don’t need the privacy challenging Google Play Services for my core apps, as they are all open source and from the F-Droid store. That being said, there is one type of proprietary apps, however, which I would really like to have on my main phone and which require these services: Banking apps.

There are various ways to get Google Play Services on custom Android Open Source ROMs, and GrapheneOS uses a particularly nifty version: The original Google Play Services and the original Google Play app store can be put into sandboxes, and GrapheneOS then puts an insulation layer around the play services to shield the operating system from it. Sounds nice!

I have to admit that I only had a very vague idea so far what the Google Play Services actually are and how they are embedded in Android. At this point, I felt that I needed to understand this a bit better before allowing it on my main phone. So after reading the GrapheneOS details on the topic and the Wikipedia entry on Google Play Services, I think I understand this much better now. So here’s my take on it:

The Android Split

Very early on in the development of Android, Google decided to split Android in two parts: Part 1 is the ‘Android Open Source Project’ (AOSP), which is free and open source and can be used by anyone. This is what all custom ROMs, including GrapheneOS, use as a base. Part 2 is the ‘Google Play Services’. This code is proprietary, closed source and requires a license from Google to pre-install on a device.

And here’s the twist: In essence, the Google Play Services (plural) are ‘just’ another Android app (singular), and this app is pretty much the front-end to all Google ‘cloud services’ and special Google ‘on device’ services. The problem: This app is special and has unrestricted access to the Android operating system. Thus, the Google Play Services app has pretty much full control over the device. But despite having such wide ranging permissions not granted to any other app, the Google Play Services app is just ‘another Android app’. This idea is important, keep this in mind for later.

So What Services?

And here are a couple of examples of what is offered by the Google Play Services app to other apps:

Popular Google cloud services used by many proprietary apps are the advertisement service that gives an app advertisements to display based on the data that Google has collected about the user.

- Apps used for things such as messaging use the Google Firebase Cloud Messaging (FCM) service to receive a notification about incoming information, e.g. incoming messages or status changes.

- Many apps that require location information also use the Google proprietary service to get non-GPS location information. The Google Play Services then collects location information, e.g. the IDs of Wi-Fi networks around the device, signal strength of those networks and potentially other local information, and sends this information to the Google cloud. There, the likely location of the device is calculated and sent back to the device.

- And then there are many many other services such as single sign-on, geo-fencing, analytics, authentication, device and software integrity assurance, etc. etc., all based on system level access to the device by the Google Play Services app and the data that Google has stored about the user in the cloud.

It’s easy to see why I wouldn’t want the Google Play Services App on my main device and even less for it to have system level access.

Sandboxing and Isolation the Rescue

So let’s come back to the banking apps I would really like to use on GrapheneOS. The problem is that pretty much all banking apps these days require access to the Google Play Services app to inquire if the device integrity is OK, i.e. that the device is not rooted, that the boot loader is locked, etc. etc. As ‘normal’ apps don’t have the rights to get such information directly, they ask the Google Play Services app to get this information on their behalf. So if the Google Play Services app is not present, those apps won’t do anything. And I can’t really have Google Play Services on my device because it has full system access and since it is closed source, nobody except Google knows what it does. So that’s the dilemma.

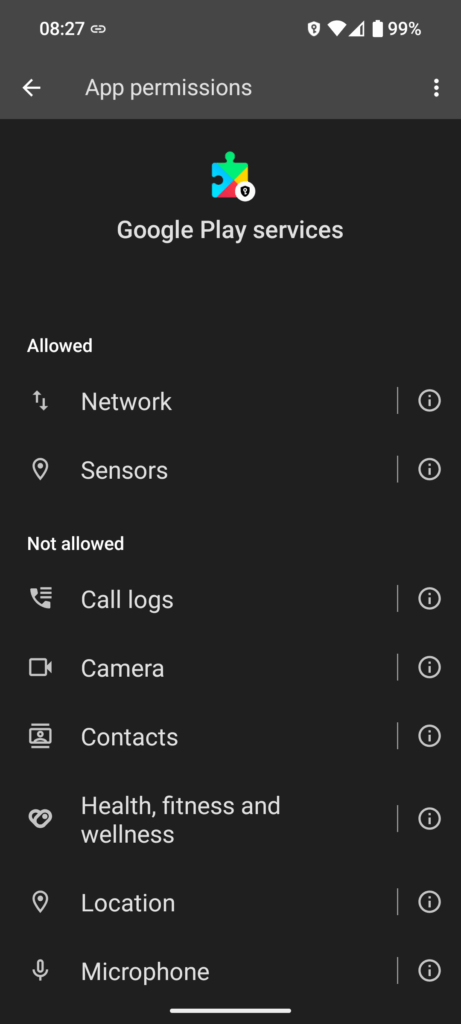

GrapheneOS gets the user out of the dilemma with the following approach: Via the GrapheneOS app store, the user can install the Google Play Services app into the standard app sandbox. In addition, GrapheneOS then puts an isolation layer around this sandboxed Play Services app that intercepts system calls. The documentation calls it the ‘compatibility layer’. In effect, the Google Play Services app thus become an app like any other without any special rights and definitely without system access. Have a look at the screenshot on the right for which permissions are given by default, and even more important, which permissions are denied to the Play Services on GrapheneOS by default. This layer around the Play Services app then performs only absolutely essential and non-privacy invading system level calls on behalf of the Play Services app. And one of those is the service required by the banking apps that check the hardware and software integrity of the device. The Play Services can of course communicate with the Google cloud backend without restrictions, but it can’t extract any local information and hence privacy is preserved.

Some Google cloud based services used by the Play Services such as for example the non-GPS location service are emulated by the insulation layer. Instead of sending WI-FI network IDs and signal strength information to Google for location calculation in the cloud, the GrapheneOS insulation layer queries its own location database in the cloud and then returns this information, plus the information about networks close to the ID that was sent back to the device. The location calculation is then performed on the device and NOT in the network, like it would be done if the Google service was used. True, the GrapheneOS project gets some private information this way, but there is no device or user identifier in the request, only the IP address of the connection can be used as an identifier if push came to shove. All of this is transparent to the Google Play Services app, which thinks it sends a request to the Google cloud, and even more so for the app that has requested the location information.

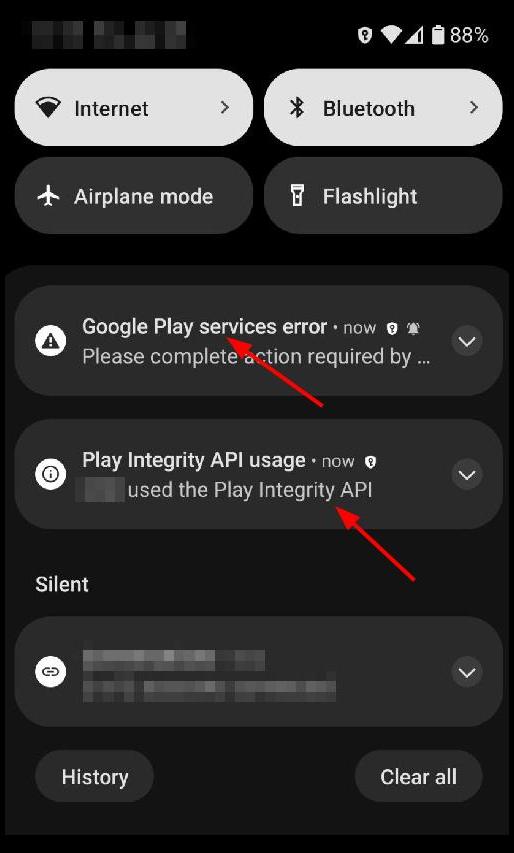

Another nice touch of GrapheneOS: By default, the OS notifies you whenever an app uses a Google Play Service app API call, so you know what is going on. The screenshot on the left gives a nice example. When I start my banking app, it access the ‘Play Integrity’ API to check that my device has a locked bootloader, no root, etc. After that, it tries to access the ‘phone’ permissions, perhaps to receive SMS, etc. By default, this permission is NOT granted to the Google Play Services app, so the OS shows a ‘Google Play services error’ which contains the info that the ‘phone’ access rights should be granted to the sandboxed Google Play Services app. But of course I wouldn’t ever give that permission, and the banking up just runs fine without it. Still, it is good to get the notification, and it puts a simile on my face every time.

Summary

All right so there we go. For me, the bottom line is: The Google Play Services are just a single app with special permissions on normal Android devices. This app delivers Google cloud services to apps and has full access to the device, with lots of privacy implications down that road. On GrapheneOS, an isolation (compatibility) layer is put around the Google Play Services app. Some Google cloud services such as the non-GPS location service is rerouted to a privacy preserving GrapheneOS alternative. Other services, such as Firebase Cloud Messaging (FCM) still go to Google, so proprietary apps, including banking apps, which use notifications for incoming requests to grant bank account transactions can work on GrapheneOS.

Yes, all of this is a compromise, and I’m willing to take it. Still, GrapheneOS yet offers even more measures that can be taken to reduce my ‘exposure’. Stay tuned for the next part in which I will have a look at the Android Work Profile and the Android Private Space to put proprietary apps and the Google Play Services app in for even more privacy.