Just because a smartphone can get an IPv6 address from a cellular network doesn’t necessarily mean that its tethering functionality is also IPv6 capable. Fortunately, I’ve noticed in practice that more and more devices that are coming to the market these days have implemented the feature. And here is how it works:

IPv4 First

When connecting a notebook or other device to the Internet via the tethering function of a smartphone the first thing the device does after connecting to the Wi-Fi access point created by the phone is to get an IPv4 address and an IPv4 DNS server address via DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol). At the same time, IPv6 capable devices also try to get a global IPv6 address which requires quite a number of steps:

Establish Local IPv6 Connectivity

At first the PC checks if its IPv6 link local address with interface-id set to the MAC address of its Wi-Fi interface is used in the network with a Neighbor Solicitation message. That’s very unlikely but one never knows. If no answer is received that device then goes ahead and uses this link local address for a number of purposes.

Find the IPv6 Router

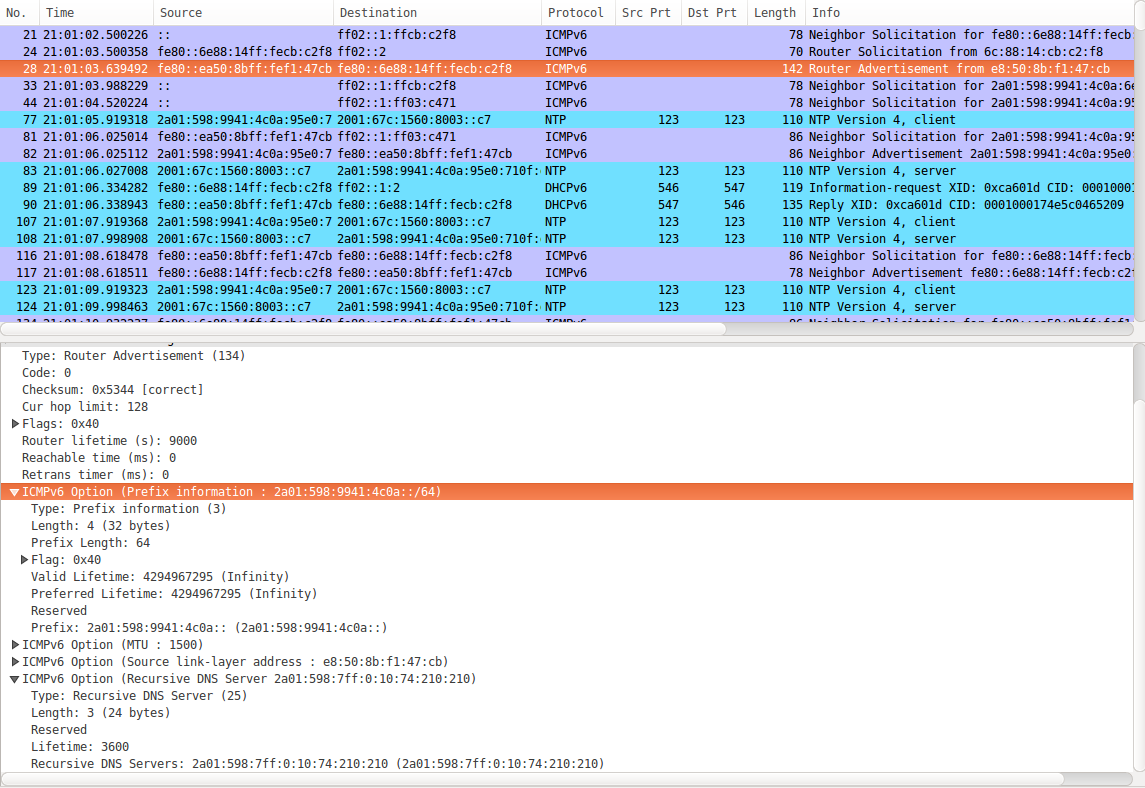

The next step then is to find out if an IPv6 router is in the network. This is done by sending a Router Solicitation Message from the link local address to the IPv6 all routers multicast address. If the UE has implemented IPv6 tethering, it (and NOT the cellular network) returns a Router Advertisement message to the link local address of the device that contains the following information:

IPv6 Prefix

MTU size (maximum packet size)

Link layer address of the router

DNS server information

Sending the DNS server IPv6 address as part of the Router Advertisement is a relatively new feature. Devices that do not implement this set the “other” flag in the message to advise the device to query for the DNS server IPv6 address with a separate message.

Constructing a global IPv6 address

With the IPv6 prefix contained in the Router Advertisement message the device then goes ahead and assembles its own IPv6 address, typically by concatenating the prefix and its MAC address as its interface id. Like for the link local address the device then sends a Neighbor Solicitation message over the network to see if another device already uses that IPv6 address.

Constructing another global IPv6 address

For privacy reasons IPv6 capable devices usually don’t use an IPv6 address with their MAC address as part of the interface id but generate a second IPv6 address with a random interface identifier. Again a Neighbor Solicitation message is sent to make sure it is unique. If no answer is received the process is complete and the device is ready to communicate with the world over IPv6.

Timing Considerations

In practice the whole process takes around 2 seconds which is slightly more than the IPv4 DHCP process. One could argue that this is an eternity as in other places optimizations are standardized to shave of a few more milliseconds of already lightning fast connection processes. I guess this is because IPv6 connection management was designed at a time when devices were mostly sitting on desks and were permanently connected to only a single network where a second more or less does not matter. For compatibility reasons, IPv6 tethering to a mobile phone has taken over the process as it was initially designed so there is no difference. From that point of view it’s a good thing so you won’t hear me complaining too loudly.