The Busch 2090 learning computer of 1981 may be a niche thing in a niche thing but over the years it every now and then sparks the interest afresh in some of those who wanted to have or actually owned this 4-bit computer back then as a teenager. 12 years ago must have been such a time for Ingo Rullusen when he decided to program a Busch 2090 emulator for the PC. Fortunately, he put the code under the GPL and put it online. Unfortunately, 12 years is enough to make it difficult to get it working again on current operating systems.

The Busch 2090 learning computer of 1981 may be a niche thing in a niche thing but over the years it every now and then sparks the interest afresh in some of those who wanted to have or actually owned this 4-bit computer back then as a teenager. 12 years ago must have been such a time for Ingo Rullusen when he decided to program a Busch 2090 emulator for the PC. Fortunately, he put the code under the GPL and put it online. Unfortunately, 12 years is enough to make it difficult to get it working again on current operating systems.

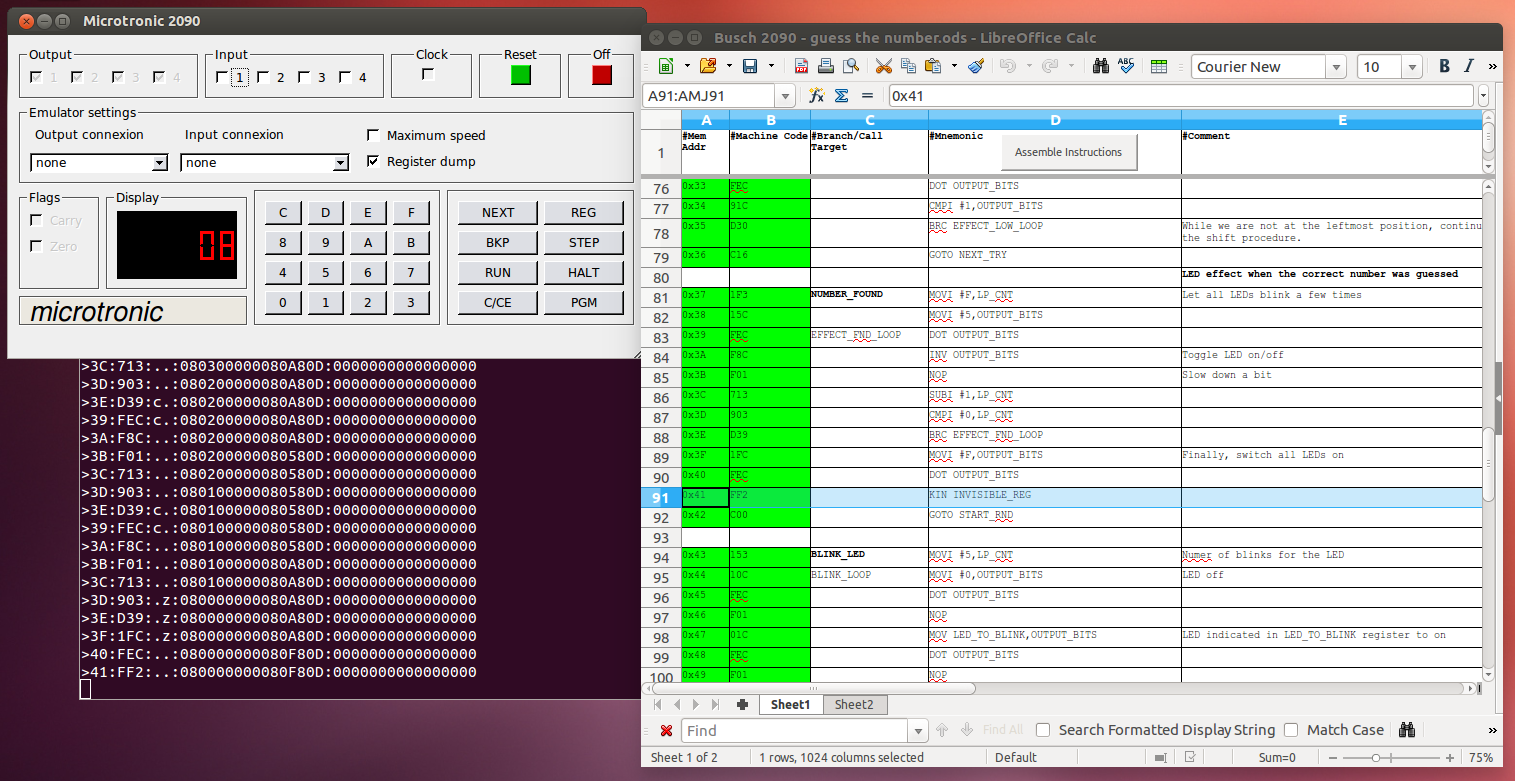

12 years is a long time in computing. Back then, Ingo programmed his emulator in C++ with a graphical front-end using the qt3 framework. 12 years later, qt is at version 5 and, you’ve probably guessed, code compilation violently ends with a couple of errors. It seems the last time qt3 was supported on Ubuntu Linux was back in 2012. Even though Ubuntu 12.04 is no longer supported by Canonical one can still download an ISO installation image and install it in a virtual machine. And that’s what I did. Even more fortunate, Canonical still has the repositories for 12.04 online so I was able to install the necessary qt and c++ runtime and development libraries. After a bit of tinkering with shell variables I was finally able to get the code compiled and running. The screenshot on the left shows the emulator on the left next to my Busch 2090 Assembler I programmed recently on the right. Programs can be read into the simulator by starting PGM-1 (load program from cassette) which opens a file manager dialog box to select a file that contains the hexadecimal pseudo-machine code.

The original emulator wants the input file to be in a very precise one 3 digit instruction without any empty lines or other gimmicks. That was a bit inconvenient for me as my assembler outputs the pseudo-machine code with empty lines by selecting the machine code column in the spread sheet and copying/pasting it into a text file. But fortunately it was not too difficult to find the part of the code responsible for reading input files so I could easily enhance the emulator for reading my output, too. In other words, the emulator is a perfect tool in combination with my assembler to explore the 2090. Another great thing for debugging is that Ingo’s emulator can output each instruction executed in an extra shell window together with the memory address and the register content before and after the execution of an instruction. That makes things a lot easier when things go south.

Obviously, carrying the torch forward is important so I’m making his code, my additions and a link to my portable VM image (1.9 GB…) available on Codeberg.