I’m from the generation that grew up just after punch cards, punched tape and mainframe computers went out of fashion and gave way to interactive programming in front of a terminal or, in my case, a computer at home. So while I was generally aware of the principle of feeding programs and data to mainframes and minis this way, I only had a hazy idea of how programs were encoded on the cards. Recently, a friend gave me a book about Assembler programming written in 1973 which did not only explain in some detail some of the machine instructions of a 1960/70 mainframe but also how Assembly language programs ended up on punch cards and finally in the memory of the computer.

I’m from the generation that grew up just after punch cards, punched tape and mainframe computers went out of fashion and gave way to interactive programming in front of a terminal or, in my case, a computer at home. So while I was generally aware of the principle of feeding programs and data to mainframes and minis this way, I only had a hazy idea of how programs were encoded on the cards. Recently, a friend gave me a book about Assembler programming written in 1973 which did not only explain in some detail some of the machine instructions of a 1960/70 mainframe but also how Assembly language programs ended up on punch cards and finally in the memory of the computer.

Programming and Punch Cards

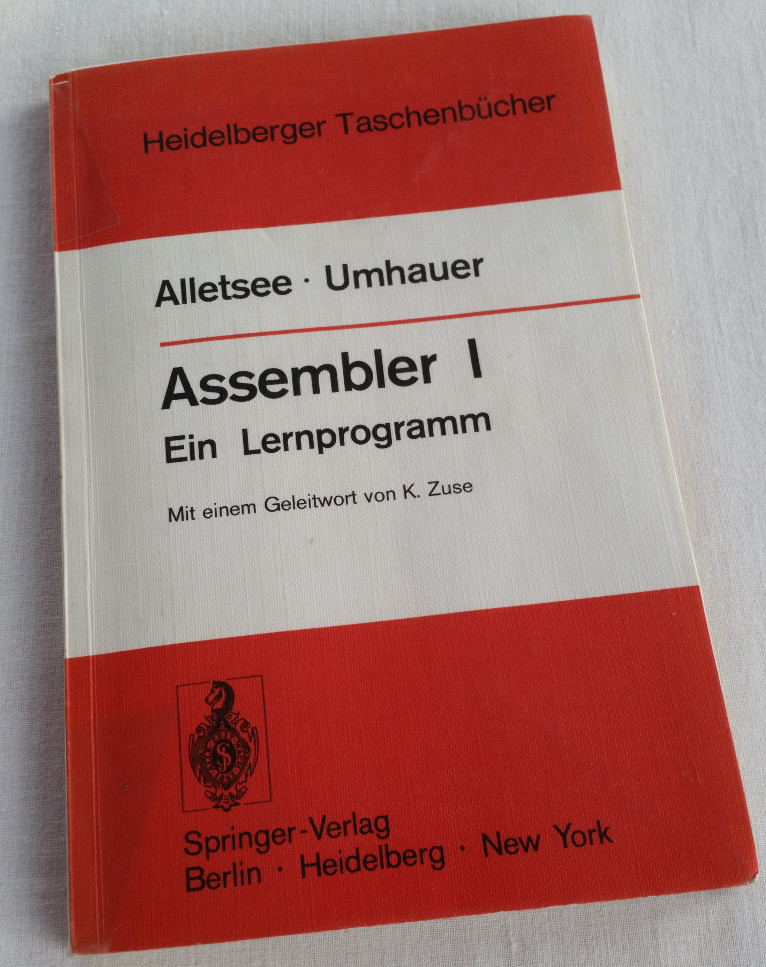

The 100 page book is called ‘Assembler 1’ by Alletsee and Umhauer in German (ISBN 3540063714) and does a great job to introduce today’s reader and historian to the world of programming a mainframe in Assembler. So from a programming point of view, my main take away is the following: Programs were written on a piece of paper at first. Once debugged on paper, each line would become a single punch card that contained the mnemonic instruction, the parameters for the instruction and finally a field for comments. Each card could hold around 80 characters so it was possible to comment the code to quite some degree. But since memory was scarce, even mainframes only had a few dozens kilobytes of memory back then, I guess commenting was quite a luxury.

Macros

Also interesting to note is that the field for the machine instruction could also hold a macro name that could do more complex tasks, such as getting data from the punch card reader or to print out some data with a single instruction rather than having to program all steps necessary for such operations by hand.

Core Dumps

In addition to instructions with comments, punch cards had to be made for any fixed data (i.e. constants) required by the program. Once done the stack of cards would be given to the mainframe ‘operator’ who would, at his convenience, put the cards into a card reader and read the Assembler program into memory. After that he would load the Assembler program from disk to convert the Assembler program into machine code. The machine code would then also be stored on the disk for later execution. Also, the mainframe could print out the assembler program next to the corresponding machine code in hexadecimal representation for debugging. Speaking about debugging, the book also talks about core dumps to debug the program when it crashed while running. Fast forward 50 years and we still have core dumps when a program crashes.

Forward by Konrad Zuse

The book also contains a forward by Konrad Zuse who is known for inventing the first programmable computer. From today’s perspective its downright from another world. He talks about the hardship of programming, about the need to be structured and precise and of his hope that this structured mentality will hopefully also spread to other areas of society that is ‘in confusion in many ways’ (‘[…] in vielerlei Hinsicht verworrenen Zeit […]’). Hm, well, I don’t think this really happened, society is still just as confused 50 years later.

Computer History in Germany

While there is quite a bit of material available about the history of the computing industry in the US, there is very little about what happened elsewhere. This book was the first one I read that changed this a bit for me as it’s quite clear that by the early 1970s, lots was done with mainframes in Europe as well and there was quite some innovation. The Assembler programming described in the book was for a Siemens 4004 mainframe, which according to this web site, is a repackaged RCA Spectra 70, which in turn was partly compatible with the legendary IBM 360 system. According to the web site, the deal between Siemens and RCA was going both ways. RCA delivered the mainframe while Siemens marketed the solution and developed and sold peripheral components back to RCA in return.

Punch cards vs. Terminals

Another interesting aspect of the book was that interactive programming wasn’t mentioned at all, it’s strictly about how to program on paper, put the program on punch cards, get it into the mainframe, let it run and get the printed output or the core dump in case it failed. Historically this is interesting, as interactivity via Teletypes must not have been uncommon in the early 1970s as e.g. the PDP-1 was already operated like this a decade earlier (see for example the book ‘Hackers’ by Stephen Levy). When you look through the material on the web site linked to above, terminals were available for Siemens 4004 systems (referred to as ‘Dialoggeräte’, i.e. ‘dialog devices’) and the architecture picture in the reference part of the book also has them included. But it looks like they were used for another purpose.

And a final thought: The book was written in 1973, home computers didn’t exist back then. But this changed only 2 years later with the Altair, soon followed by a myriad of other home computers. At the step of a quantum leap…