A few weeks ago I asked the question here if anyone knew what the 4 dots in the GSM logo actually stood for. A few people contacted me with good suggestions what the dots could stand for, which was quite entertaining, but nobody really knew. On the more serious side, however, a few people gave me interesting hints that finally led me to the answer:

A few weeks ago I asked the question here if anyone knew what the 4 dots in the GSM logo actually stood for. A few people contacted me with good suggestions what the dots could stand for, which was quite entertaining, but nobody really knew. On the more serious side, however, a few people gave me interesting hints that finally led me to the answer:

On gsm-history.org , a website of Friedhelm Hillebrand & Partners, and article is published that was written Yngve Zetterstrom. Yngve's been the rapporteur of the Maketing and Planning (MP) group of the MoU (Memorandum of Understanding group, later to become the GSM Association (GSMA)) in 1989, the year in which the logo was created. The article contains intersting background information on how the logo was created but it did not contain any details on the 4 dots. After some further digging I found Yngve on Linkedin and contacted him. And here's what he had to say to solve the mystery:

"[The dots symbolize] three [clients] in the home network and one roaming client."

There you go, an answer from the prime source!

It might be a surprising answer but from a 1980's point of view it makes perfect sense to put an abstract representation for the GSM roaming capabilities into the logo. In the 1980's, Europe's telecommunication systems were well protected national monopolies and there was no interoperability of wireless systems beyond country borders, save for an exception in the Nordic countries, who had deployed the analogue NMT system and who's subscribers could roam to neighboring countries. But international roaming on a European and later global level was a novel and breakthrough technical feature and idea in the heads of the people who created GSM at the time. It radically ended an era in which people had to remove the telephone equipment installed in their car's trunks (few could afford it obviously) if they wanted to go abroad, or to alternatively seal the system or to sign a declaration that they would not use their wireless equipment after crossing a border. Taking a mobile phone in your pocket over a border and use it hundreds or thousands of kilometers away from one's one home country was a concept few could have imagined then. And that was only 30 years ago…

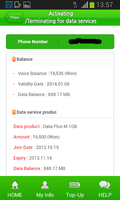

P.S.: The phone in the image with the GSM logo on it is one of the very first GSM phones from back in 1992.