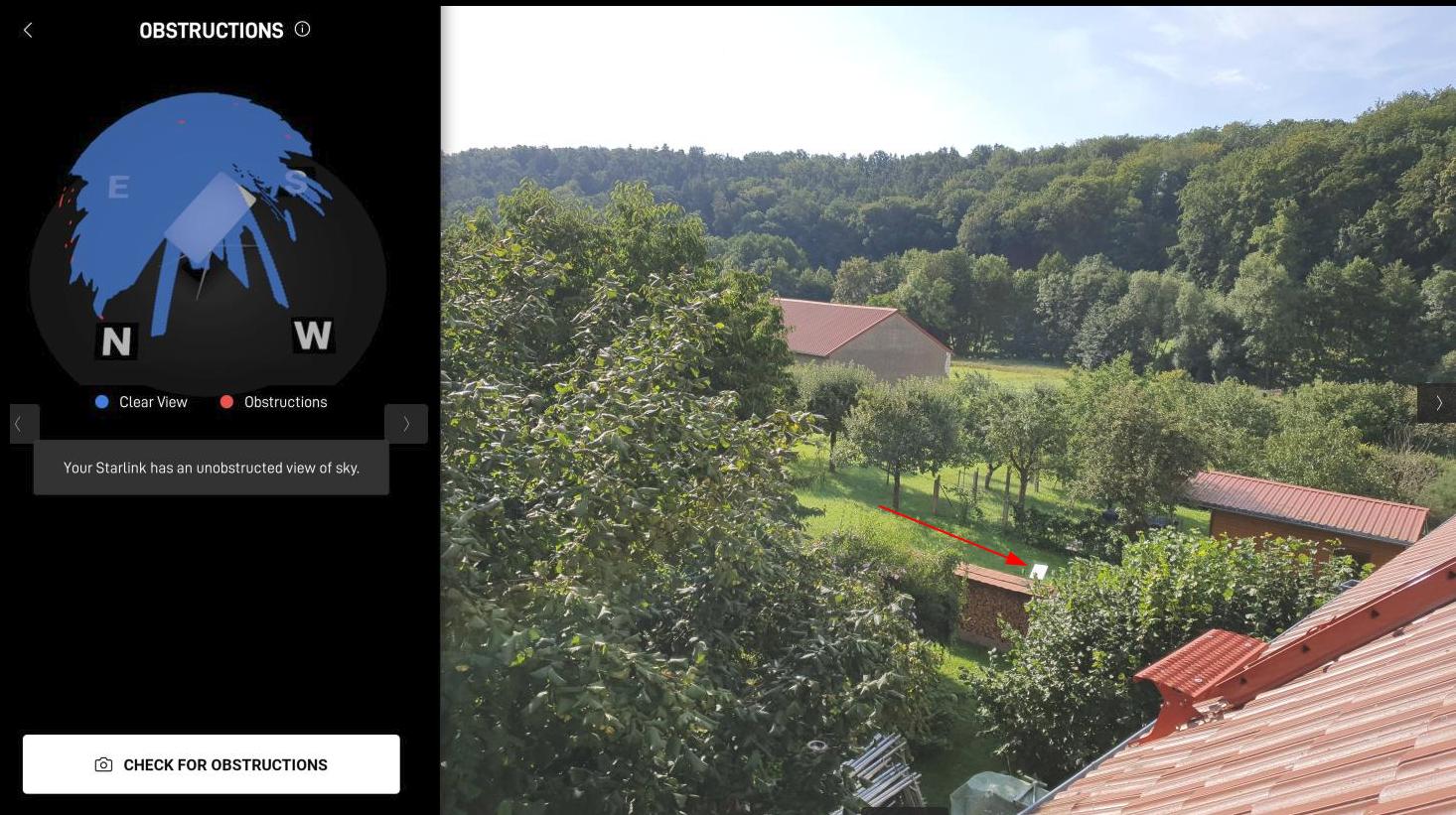

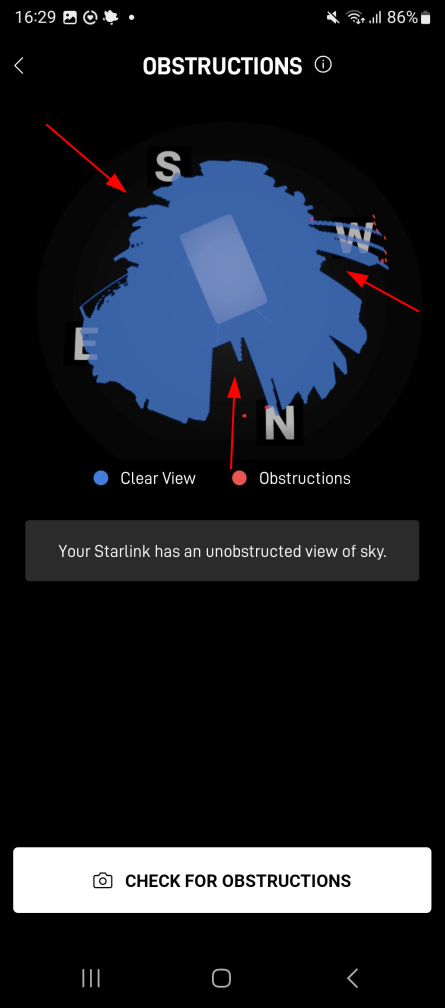

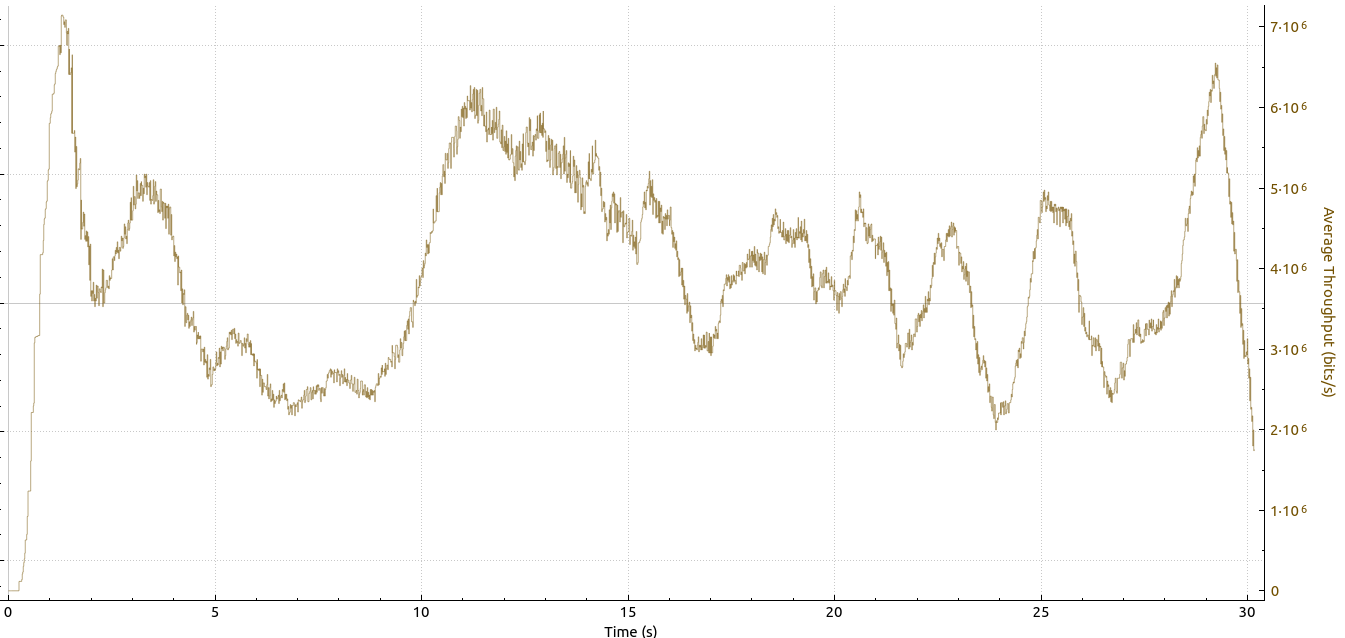

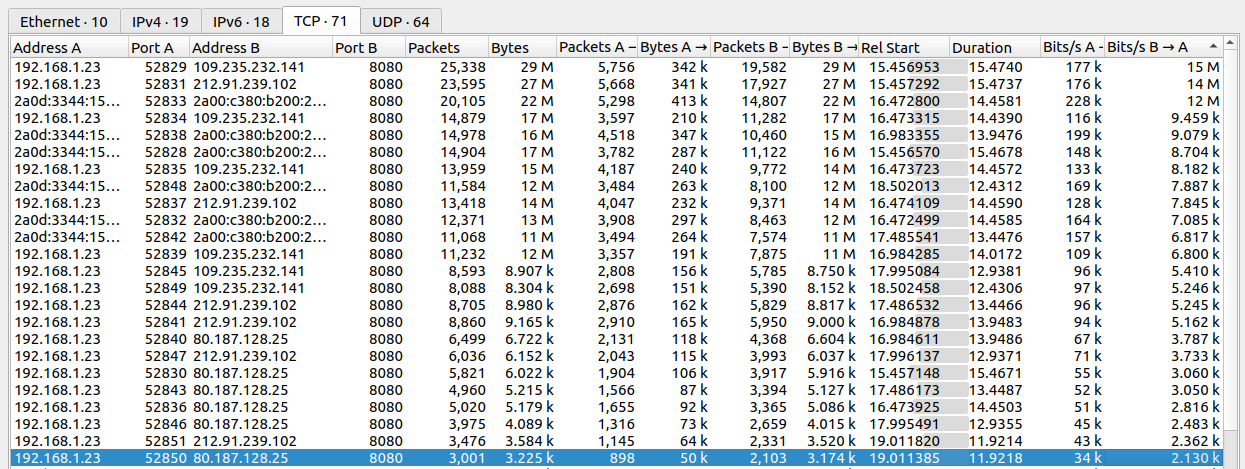

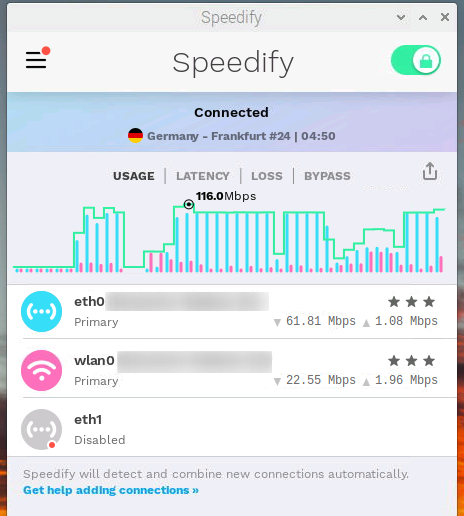

Every now and then I am at places at the fringe of the observable Internet where I only have slow, weak and unreliable connectivity. Typically, though, there are several of such networks to chose from, for example because network operators share towers. Wouldn’t it be great if one could combine those networks to get some more speed and reliability out of it? Until recently, I wasn’t aware of an easy way to do this. But then I noticed a world traveler on Twitch who regularly streams while driving, even at remote places. His solution: Combining Internet connectivity from a Starlink dish on his RV’s roof and two cellular connections with a software called Speedify on a Raspberry Pi. Hm, sounds like this is just what I need.

Continue reading Multi-Path Backhaul with Speedify – Part 1 of 2